A Level Economics success – developing chains of reasoning

14 March 2023

Sarah Phillips, Business and Economics Subject Advisor

Economics is a social science and therefore, as with most written subjects, in order to be able to access the highest grades, students are required to demonstrate higher order skills of analysis and evaluation in relation to economic problems and issues.

Students need to use their knowledge and understanding to develop logical and coherent responses to economic problems. Developed arguments require a continuation and, as the description suggests, a development of lines of discussion rather than several individual points that are not explained or exemplified. Therefore students need to use ‘chains of reasoning’. These are also referred to as ‘chains of argument’, or ‘chains of analysis’.

Being able to develop multi-stage chains of thought will almost certainly be the differentiator in extended response questions, allowing access to the higher levels of response, but is also a skill required in some multiple choice questions. It’s therefore important that we practise these with our students as early in the course as possible.

Chains of reasoning

As mentioned, chains of reasoning are also referred to as chains of argument, or chains of analysis. These are a key part of developed analysis. Students may find it easier to consider this development as a series of logical steps, and so I will refer to these as ‘steps’ in the examples below.

Multi-step chains of reasoning – examples

No chain of reasoning

- An increase in income tax lowers economic growth (assertion)

2 step reasoning

- An increase in income tax shifts Aggregate Demand (AD) to the left (Step 1), reducing economic growth (Step 2)

3 step reasoning

- An increase in income tax reduces consumer spending (Step 1), leading to a shift left of AD (Step 2), reducing economic growth (Step 3)

4 step reasoning

- An increase in income tax reduces consumer incomes (Step 1) and therefore leads to less consumer spending (Step 2). This causes a shift left of AD (Step 3), reducing economic growth (Step 4)

4 step reasoning supported with data / evidence / context

- An increase in income tax reduces consumer incomes (Step 1) leading to less consumer spending (Step 2). As consumer spending in the UK / Fig x is the largest component of AD (data / evidence / context), this causes a shift left of AD (Step 3), reducing economic growth (Step 4).

4 step reasoning supported with data / evidence / context and diagram

- An increase in income tax reduces consumer incomes (Step 1) leading to less consumer spending (Step 2). As consumer spending in the UK / Fig x is the largest component of AD (data / evidence / context), this causes a shift left of AD, from AD1 to AD2, and a new macroeconomic equilibrium of Y2, PL2, as shown on the diagram. (Step 3 supported by diagram). This reduction in Y represents a reduction in GDP and growth. (Step 4 supported by diagram)

Multi-step reasoning in multiple choice questions (MCQs)

MCQs mostly assess knowledge and understanding (AO1) and application (AO2), but some may also assess analysis (AO3) and evaluation (AO4).

Students need to be prepared to use multi-stage reasoning to reach the correct answer. MCQs may require students to demonstrate higher order skills in a range of ways such as rearranging formulas, using multi-stage calculations and/or multi-stage reasoning.

Examples of these can be taken from the June 2022, Paper 3. The examiner’s report makes reference to these:

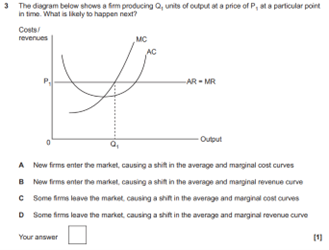

Question 3:

Multi-stage reasoning was required in this question: first a recognition that the diagram represented a firm operating in a perfectly competitive market; second that it was earning abnormal profit; third that abnormal profit attracts new entrants; fourth that the entry of new firms shifts down the AR = MR line.

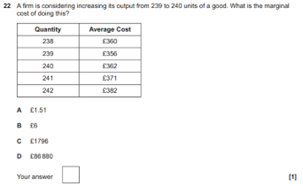

Question 22:

This question required a multi-stage calculation from average cost to total cost to the change in total cost and proved difficult for many.

So how can we help our students with this?

Here are a few practical ideas that you could incorporate into your lessons.

- Model good reasoning.Show students examples of well-structured arguments and reasoning chains in example work. You could ask them to highlight the different steps, as in the worked example above, or separate them out with arrows to illustrate the continued flow, rather than several new points.

- Use graphic organisers.Graphic organisers such as mind maps, flowcharts, and diagrams can help students visualise the logical connections between ideas and see how they fit together.

- Encourage outlining.Ask students to create outlines before they start writing. This helps them organise their thoughts and identify any gaps in their reasoning.

- Scaffold writing tasks.When setting writing tasks, break them down into smaller, more manageable steps. This allows students to focus on one aspect of reasoning at a time, such as identifying evidence or making connections between ideas.

- Peer review.Have students review each other’s writing and provide feedback on the strength of their reasoning chains. This can help them see how others approach reasoning and give them ideas for improving their own work. Encourage students to work collaboratively with their peers to develop and refine their arguments.

- Targeted feedback.Provide students with feedback on their writing, focusing specifically on the strength of their reasoning chains. Give specific examples of where their reasoning was strong and where it could be improved.

- Encouraging debate.Debates can be an excellent way to practise chains of reasoning. A speaker might use a chain of reasoning to connect evidence to a conclusion. For example, they might present evidence showing that a particular policy has been successful in other countries, and then use this evidence to argue that the policy would be effective in their own country. A chain of reasoning can also be used to build a logical argument. For example, a speaker might start by making a general statement, such as “climate change is a serious threat”, and then use a chain of reasoning to support this statement with evidence, such as the rise in global temperatures and the increase in natural disasters.

-

Chains of reasoning can also be used to refute counterarguments. For example, a speaker might acknowledge a potential objection to their argument, such as “some people argue that we should focus on economic growth instead of environmental protection”, and then use a chain of reasoning to explain why their argument still stands. As a bonus, debates are also a great way to understand and develop evaluation skills!

For more information and examples of question types and responses, refer to the examiners’ reports and candidate exemplars on Teach Cambridge which provide helpful comments, advice and guidance on the papers and question types, after every summer series.

Stay connected

Share your thoughts in the comments below. If you have any questions you can email support@ocr.org.uk, call us on 01223 553998 or tweet us @OCR_BusEcon. You can also sign up to subject updates to keep up-to-date with the latest news, updates and resources.

About the author

Sarah joined the Business and Economics team in September 2022. She has over 20 years’ experience as a teacher of Business, Economics and Finance and in leadership roles including Head of Department, Head of Sixth Form and Assistant Principal. She has been an assessor for A Level Economics and holds a degree in Business Economics and the RSA Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults (CELTA).

Related blogs